In St. Thomas, thought and holiness, theology and prayer, reasoning and mysticism, study and love of God are profoundly intertwined. Thus, he became the holiest wise man the Church has ever known.

When we hear St. Thomas Aquinas spoken of, the theologian that marked Catholic thought for all time comes to mind. We are impressed with the depth of his reasoning, the breadth of the subjects he covered and, especially, his monumental ability to harmonize Faith and reason, theology and philosophy which stands unsurpassed to this day.

But this prompts a question: was he nothing more than a brilliant intellectual? For, in certain settings, the study of his work focuses only on his originality and clarity of reasoning, setting aside everything related to his heroic practice of virtue.

Yet, only acknowledging the intellectual side of St. Thomas greatly diminishes this luminary figure. He was first and foremost a great Saint, and we do not hesitate to affirm that his theology, his philosophy and his masterful didactics were the result of a factor that transcended lucidity of reason and dedication to study. Thought and sanctity, knowledge and prayer, logic and mysticism, study and love of God are profoundly intertwined in this illustrious Dominican. Had he failed to attain the heights of holiness and interior life, his intellectual capacity would never have attained such lustre.

In the following lines, we will endeavour to sketch out his life in order to provide a few illuminating flashes of the union between theology and holiness that characterized this great soul.

Called to the Order of Preachers

St. Thomas was born in Roccasecca, near Naples, in the bygone years of 1224 or 1225. When he was still very young, he went to live with the Benedictines of Monte Cassino and the family expected that, to honour the noble Aquino lineage, he would eventually become the superior of the famous abbey.

But God had different plans…

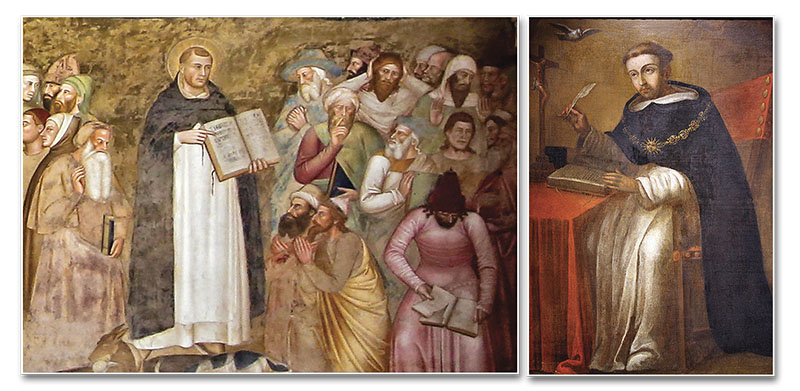

After spending some years with the Benedictines, Thomas transferred to Naples, where he attended the university founded by Frederick II. It was at this time that his vocation awakened. “Thomas was in fact attracted by the ideal of the Order recently founded by St. Dominic,”1 and decided to join it.

Friar Giovanni de San Giuliano, a Dominican of this Italian city, forged a friendship with the young Thomas and, over three consecutive nights, saw him in dreams, his face shining like the sun, scattering rays that lit up everything around him, even Friar Giovanni himself. The message was clear: “The sun of Aquino”2 should enter the Order of Preachers.

After he was clothed in the Dominican habit, Friar Thomas had to face the staunch opposition of his family. Appalled at his entrance into a mendicant Order they even resorted to violence in an attempt to dissuade him. Nevertheless, after some time had passed, they realized their efforts were in vain, and let him fly freely to the firmament of prayer and sacra doctrina.

Study as a means of attaining sanctity

He was first sent to Paris, but soon after he set out for Cologne to study the studium generale of the Order, and there he became acquainted with a great master in whose school he was to be formed: St. Albert the Great. The connection between them was immediate. It is said that during classes, as he listened to the marvellous teachings of St. Albert, Thomas rejoiced at having found what he sought and “he began to be extraordinarily silent, assiduous and devout in prayer.”3

The dedicated student united the spiritual life with passion for intellectual work. For him study had a refined religious character that was essential to his vocation “as a member of an Order to which St. Dominic, in founding it, had assigned study as one of the specific means for attaining the objectives of religious life.”4

Thomas considered the study of sacred theology as something very important for contemplative life and apostolate. Later, in the Summa Theologica5 he would declare that study illuminates the divine reality and guards against customary errors into which contemplatives unfamiliar with Sacred Scripture fall. He also said that study is necessary for preaching and other similar ministries. Finally, he noted how it serves as a means of penance and purification, since it preserves the soul from lascivious thoughts, mortifies the flesh by the effort it demands, causes love of wisdom to prevail over earthly goods, preventing the coveting of riches, and is an assurance of obedience for those who dedicate themselves to it in virtue of their religious profession.

Additionally, study must be ordained to knowledge, which must be governed by charity,6 for this leads to apostolate and the salvation of souls. For Thomas, study was the means of attaining sanctity within the way indicated by St. Hilary: “I am aware that I owe this to God as the chief duty of my life, that my every word and sense may speak of Him.”7

Professor at the University of Paris

St. Albert the Great proposed St. Thomas as a candidate for professor at the University of Paris, the hub of study in medieval Europe and, therefore, in the world at that time. He was only 23 years old and there he attained admirable success. The students flocked to his classes. He taught new themes, raised theological questions to debate with the students, explained problems of theology, philosophy and general knowledge in clear and original terms It was evident that a new light had been lit in the universe of divine science.

In an audience dedicated to him, cited above, Benedict XVI recounts that “One of his former pupils declared that a vast multitude of students took Thomas’ courses, so many that the halls could barely accommodate them; and this student added, making a personal comment, that ‘listening to him brought him deep happiness.’”8

What was at the root of this attraction? “The charm of the young professor was due not only to his knowledge and his method, but also to the honesty, nobility and purity that flowed from his personality. […] Thomas exhaled the fragrance of genuine purity by his presence and his words: many called it sanctity. Purity and sanctity which translated into divine and human wisdom, made of him a master of doctrine and life.”9

Mystical and intellectual life

Among his habits, was that of visiting the Most Blessed Sacrament before lecturing. His mystical life was so penetrating that Friar Reginald of Piperno, his constant companion – according to the Order of Preachers, one should never be without the company of another brother –, sometimes had to prompt him to eat, for the Saint not uncommonly tarried in heavenly ecstasies.

Once, in friendly conversation with his students, he commented, without a trace of vanity, that he always fully grasped any work he studied and transcended it, but that he used this gift to be a herald of the Lord’s glory and grace. In this he was assisted by his prodigious memory, so that having read a book once, he invariably remembered its entire contents.

When Pope Urban IV requested him to summarize the commentaries of the Holy Fathers on the Gospels in one volume, Thomas sought books in the archives and libraries of a variety of convents. As he read them they became so etched in his memory that, later, while composing his work – Catena Aurea in Evangelia –, the previously consulted texts were as if right before his eyes.

A paradigmatic sign of this union between study and contemplation is a episode narrated by most of his biographers.10 During his tenure as professor in Paris, he set out on a stroll through the neighbourhoods with his students. When they stopped for a short rest, a young student said to him:

“Master, what a beautiful city Paris is!”

“It is truly beautiful,” Thomas replied.

“Ah! If it were yours…”

“And what would I do with it?”

“You could sell it to the King of France and, with the money, you could build the convent that the Dominicans need.”

Thomas responded:

“To tell you the truth, I would prefer to have the commentary of St. John Chrysostom on the Gospel of Matthew… The city and the obligations it would bring, would be, for me, an impediment to study and contemplation.”

There is another famous episode that occurred in the palace of the glorious St. Louis IX. Thomas enjoyed the friendship of the King of France and, since he was in Paris, the monarch invited him to dine, along with the Prior of the Dominicans. In the middle of the meal, the Saint became absorbed in thought. Suddenly, he slammed the table, and exclaimed:

— Ergo conclusum est contra Manichæos!

He had found the argument needed to finish a demonstration against the errors of the Manicheans. The Prior hastily removed his cape, to bring him back to his senses, saying:

— Attention, master, we are at the table of the King of France…

“But, with noble courtesy, the holy king ordered a page to provide him with whatever he needed to commit all of his thoughts and discoveries to writing.”11

The crowning work of his sacred knowledge

The works of St. Thomas are bountiful, insightful and profound – it would be impossible to enumerate them here. But the Summa Theologica merits special mention, since it is arguably the crowning work of his sacred knowledge. He composed it principally for his novices in study, as a study manual.

In this theological monument, his great lucidity in harmonizing Faith and reason shines brightly. There are many commentators on the Summa Theologica, but no one has surpassed its author in clarity. In it Thomas studies the divine nature, exploring its immensity and attributes, in a wonderfully transparent style.

In the first part, he ascends the peaks of sacra doctrina and delves into the most august of all subjects, the Blessed Trinity and the distinction between the Divine Persons. He touches on the question of the Angels and shows us the beauty of the angelic world and its hierarchies. On man, he summarizes the creation and reveals to us this small universe with a delicacy and profundity that could be called divine.

The second part is dedicated to morality: human acts, the conditions that modify them, the passions, the habits, the virtues, the vices and sins. He also speaks to us of natural law, of human law and Divine Law, and writes extensively on the great subject of grace, the source of justification.

The Angelic Doctor consecrates the third part to the Incarnation of the Word and the Sacraments. He studies Baptism and Confirmation, and reaches an apex in discussing the Eucharist. The exposition is a masterpiece. He sets to work on Penance, but his hand is stayed; death interrupts his work. Someone might ask: why? It is a mystery…

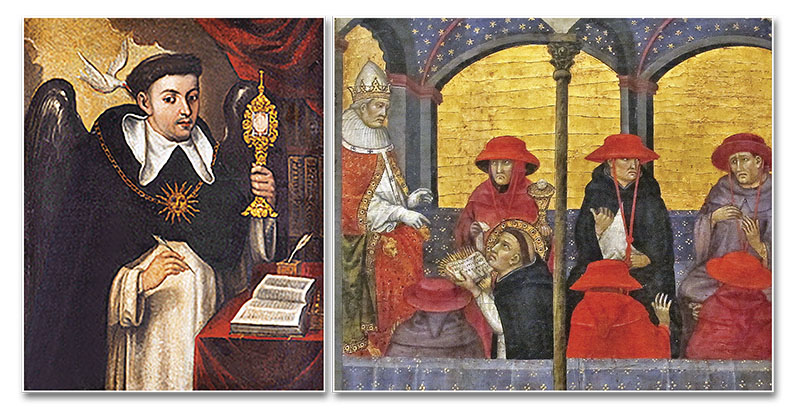

Devotion to the Holy Eucharist and Our Lady

The font of his wisdom was the Most Blessed Sacrament. “When he celebrated, the Holy Doctor often experienced such ecstasies, that his face became wet with tears; it was then that his soul abundantly harvested lights and graces, of which this august Sacrament was the source.”12

The famous hymns he composed were the fruit of his deep and fervent Eucharist devotion. Among the most well known are O sacrum convivium, which sings the praises of the sacred banquet of the Eucharist, in which the pledge of future life is given; Pange lingua, which summarizes the mystery of Faith in insightful and concise doctrinal terms, and which the Church has chosen for the rite of Eucharistic Adoration; Sacris solemniis, which tells the story of the Last Supper with lyrical accents; Lauda Sion, in which faith, love and theology are blended!

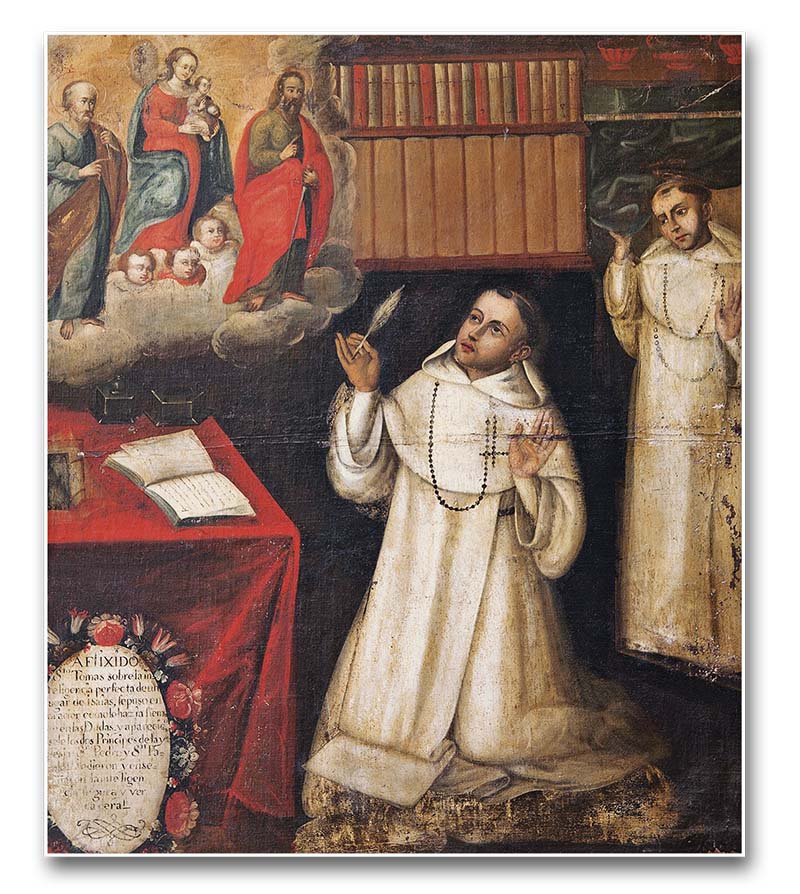

This great theologian also devoted tender love to the Blessed Virgin Mary, to whom, he said, he owed everything he had received from God. According to Friar Reginald, and confirmed by the Saint himself, “this amiable Sovereign appeared to him a few days before his death and gave him full certainty regarding his life, his doctrine and his final perseverance.”13

The twilight of this great Saint’s life

While in Naples on December 6 of 1273, feast of St. Nicholas, the Holy Doctor had a revelation during the celebration of Mass that completely transformed him. He was preparing the Treatise on Penance, included in the third part of the Summa. He broke his pen and he would neither write nor dictate anything more. Friar Reginald said to him that his writings were very important for the glory of God and for Christianity. But, St. Thomas would not change his mind.

He later gave the reason: “Reginald, my son, I am going to tell you a secret, but I implore you, in the name of almighty God, by your fidelity to our Order and by the affection you have for me, not to reveal this to anyone, while I am alive. The end of my work has arrived; everything that I have written, everything that I have taught seems to me like so much straw after what was revealed to me. Henceforth, I hope from the goodness of my God that the end of my life follows upon that of my work.”14

His superiors, judging him to be very weary – today we would say very stressed – ordered him to visit his sister, the Countess of Sanseverino, whom he greatly loved. Thomas obeyed; however, he said almost nothing to his sister who, in surprise, asked Friar Reginald what had happened with her brother, for he seemed like a changed person.

At that time, Pope Gregory X convoked a general council in the city of Lyon with the principal objective of bringing back the Eastern Greek Church to the bosom of Catholicism. One of the first to be called by the Pope was St. Thomas Aquinas, for he “was considered one of the wisest and holiest men in the world.”15 Word had spread throughout ecclesiastical settings that the Pope wanted to make him a Cardinal.

The date for the opening of the council was marked for May 1, 1274. On the way to Lyon, in harsh winter conditions, accompanied by the faithful Friar Reginald, he visited his niece, the Countess of Ceccano, and while at her residence he completely lost his appetite. The doctors of this lady attended him, but they were unable to improve his condition. Despite this, he decided to continue his journey.

When he arrived at the Cistercian Abbey of Fossanova, he went immediately to the chapel to adore the Blessed Sacrament, and there it seemed to him that the hand of the Lord rested upon him. He said: “Reginald, my son, this is the place of my repose.”16 Those who heard him began to weep; St. Thomas would take to bed and never rise from it again.

The Cistercians asked him to comment on the Song of Songs, from his bed, to which he replied that he could not, as he did not have the spirit of St. Bernard. But he finally acceded, due to his hosts’ insistence.

Feeling that his last hour was approaching, he asked to make a general Confession and to receive Holy Communion. The abbot, surrounded by his religious, entered Thomas’ room. He asked them to place him on the floor so that he could receive Our Lord in a humbler position, and he made an act of faith in the Eucharist. The next morning, he asked for the Anointing of the Sick and all those present testified that his face became illuminated by sweet joy.

In great peace he expired on March 7, 1274. A monk who prayed in the chapel “was taken by a mysterious sleep and, in a dream, saw a star of admirable brightness rise from the abbey to Heaven.”17

Glorification of St. Thomas and his doctrine

The works of St. Thomas spread throughout the universities and houses of study of the time, and his doctrine gradually gained acceptance in all of Europe.

A Jesuit contemporary of St. Ignatius, Fr. Pedro de Ribadeneira, said of St. Thomas: “There is nothing in theology and philosophy so difficult that he has not made accessible, nothing so hidden that he has not revealed and explained with such precision and brevity that the phrases are as many as the words, and in a few lines he says in substance what other doctors write in many. All of this is done with admirable clarity, distinction, disposition, concordance and connection between things, that, just like physical light, it seems that his doctrine truly is the light enabling one to see and understand. On the other hand, it is so well-grounded, solid and secure that there is no place to stumble or to fall.”18

Numerous Popes have eulogized the teaching and the holiness of the Angelic Doctor. St. Pius V, with the Bull Mirabilis Deus, dated April of 1567, declared him Doctor of the Universal Church. Leo XIII, in a letter dated September 20, 1892, to the Master General of the Dominicans, Fr. Andrew Frühwirth, “expressed his profound conviction and resolute will to guide the intelligences by the doctrine of St. Thomas and the hearts by the Rosary, that is to say, to bring back wayward humanity to the paths of truth and true life – in viam veritatis et veræ vitæ – by these two most efficacious means of salvation.”19 Additionally, with his Encyclical Æterni Patris he restored Christian philosophy in accordance with perennial Thomist principles, from which they had strayed with the passing of time. And throughout the twentieth century there was abundant praise coming from the Chair of St. Peter which is too lengthy to enumerate here.

Yet, perhaps the life and work of the Angelic Doctor is best summed up by the famous aphorism of Cardinal Bessarion: “St. Thomas is the wisest of Saints and the holiest of wise men.”20 There is no greater praise on this earth for one who dedicated his life to God, to his holy Mother, to his Order and to the study of sacred theology.²

Notes