On the Solemnity of All Saints, the Church invites us to reflect on our heavenly brethren with hope, as a stimulus for us to follow the path began at Baptism to the end, reaching complete happiness in the glory of the beatific vision.

Gospel of Solemnity of All Saints

1 When Jesus saw the crowds, He went up the mountain, and after He had sat down, His disciples came to Him. 2 He began to teach them, saying:

3 “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven. 4 Blessed are they who mourn, for they will be comforted.

5 Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the land. 6 Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied. 7 Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy. 8 Blessed are the clean of heart, for they will see God. 9 Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. 10 Blessed are those who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven. 11 Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and utter every kind of evil against you falsely because of Me.

12a Rejoice and be glad, for your reward will be great in Heaven” (Mt 5:1-12a).

I – The Saints, our Heavenly Brethren

In the Solemnity of All Saints, the Church commemorates all those who enjoy full possession of the beatific vision, including those not canonized. The Mass’ Entrance Antiphon extends this invitation: “Let us all rejoice in the Lord, as we celebrate the feast day in honour of all the Saints.”1 Yes, we rejoice because, in the broadest sense, all those who are part of the Mystical Body of Christ are saints—not only those who have already won heavenly glory, but also those paying their temporal debt in Purgatory, and even those living on this earth of exile, who are in God’s grace. Whether we exist in this world as members of the Church Militant, or in Purgatory as the Church Suffering, or in eternal happiness as the Church Triumphant, we all make up one and the same Church. And, as her children, we are brothers, as St. Paul says to the Ephesians: “you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the Saints and members of the household of God” (Eph 2:19).

The Saints strengthen us and give us their good example

This is why the Preface for this Solemnity prays, “We celebrate the festival of your city, the heavenly Jerusalem, our mother, where the great array of our brothers and sisters already gives you eternal praise. Towards her, we eagerly hasten as pilgrims advancing by faith, rejoicing in the glory bestowed upon those exalted members of the Church through whom You give us, in our frailty, both strength and good example.”2

II – We are Called to Gather Together in Heaven

The first reading, from Revelation (Rv 7:2-4, 9-14), is beautiful and its symbolism is rich and complex. Let us focus on just two aspects that relate specifically to this celebration. “Then I saw another Angel ascend from the rising of the sun, with the seal of the living God, and he called out with a loud voice to the four Angels who had been given power to harm earth and sea, saying, ‘Do not harm the earth or the sea or the trees, till we have sealed the servants of our God upon their foreheads’” (Rv 7:2-3). This marvellous passage illustrates how God will only bring about the end of the world once all the places in Heaven have been occupied and the multitude of the blessed is complete. We see how, despite the offenses committed against Him, before punishing the earth, God cares for His Saints, His chosen ones.

St. John then continues: “I heard the number of the sealed, a hundred and forty-four thousand sealed, out of every tribe of the sons of Israel” (Rev. 7:4). The number of those who follow the Lamb wherever He goes (cf. Rv 14:4) is symbolic, for the number of Saints in Heaven is incalculable. When creating Empyrean Heaven—which, according to St. Thomas Aquinas,3 was the first creature to come forth from God’s hands, together with the Angels—He had, from all eternity, planned to populate it with other intelligent beings who, along with the angelic spirits, would be partakers in the divine nature, and therefore participants in His eternal happiness.

This is the appeal made to us in today’s Liturgy: to desire and to embrace the path of holiness so as to number among that one hundred and forty-four thousand.

The predominance of evil after original sin

With original sin, however, man began to take an intemperate interest in material things, gradually forgetting God. The fight between good and evil, between carnal pleasure and God’s call to holiness, was established on earth, and evil invaded human relationships with extraordinary virulence, for evil is dynamic, while goodness is simply self-diffusive.4 Indeed, were it not for the help of grace, evil would prevail completely in us, overpowering the good.

From the first Saint to Our Lord Jesus Christ

This became obvious after Adam and Eve’s departure from the Garden of Eden, in the story of their first two offspring, Cain and Abel. Abel was a child of light, upright and just, whose sacrifices offered to God were accepted with benevolence (cf. Gn 4:4). Cain, in contrast, harboured the nefarious vice of envy in his soul, which, when it reached its peak, drove him to kill his brother, shedding innocent blood. Then, filled with bitterness and misery as a consequence of his sin, Cain wanted to flee from the face of the Lord, with that illusion characteristic of the sinner, who thinks he can hide from God as one hides from human eyes (cf. Gn 4:8,14).

With what horror Eve must have taken her son’s corpse into her arms, coming face-to-face, for the first time, with the effects of the sin committed in Paradise! But Abel’s soul, at the moment it separated from his body, went to the Limbo of the Fathers to await the coming of the Saviour who would open the gates of Heaven. Preceding his parents, he headed the cortège of the Saints; those who gradually made up the number of those who would pass from this life to eternal beatitude.

The Incarnation of the Word brought a multitude of Saints to the world

However, the Incarnation of the Word and His visible presence among men brought a multitude of Saints to the world, from the Holy Innocent martyrs to the Good Thief, who, having beseeched mercy, obtained from God’s own lips the reward of being forgiven and sanctified: “Today you will be with Me in Paradise” (Lk 23:43). When Jesus expired on the Cross, His soul descended into Limbo, where the first one to receive Him was undoubtedly St. Joseph, who had been waiting for Him there for some years. But it was the day of His glorious Ascension that the Redeemer took this jubilant cohort of the just with Him into Heaven, which thus began to be populated. Later, to the delight of the Blessed, Mary Most Holy was assumed, body and soul, and was crowned Queen of the universe.

The doors of holiness were opened wide

Over the twenty centuries of Church History, those eternal dwellings would welcome martyrs, doctors, confessors… for Our Lord Jesus Christ had definitively opened the doors of holiness to all men, with the outpouring of His grace and His new doctrine endowed with authority (cf. Lk 4:32, Mk 1:22).

The synopsis of this doctrine is the Sermon on the Mount, whose centre is the Gospel chosen for this Solemnity (Mt 5:1-12); the proclamation of the Beatitudes. These are, in fact, the summary of all Catholic morality, every way of perfection, all practice of virtue. When, on this day, we celebrate the throng of Saints who dwell in Celestial Paradise, it is because they accomplished in their life what the Divine Master outlined as the way of beatitude.

Having reviewed this Gospel on other occasions,5 we will limit ourselves here to giving a summary of the teachings it contains, in light of today’s solemnity.

The contrast between the Old Law and the New

Let us first consider the contrast between this scene of the Sermon on the Mount and another important transmission in sacred history: the promulgation of the Old Law on Mount Sinai (cf. Ex 19-23). It seems that Our Lord purposely wished to establish a comparison between these two episodes in order to highlight the beauty of the New Law He came to bring, which was the most perfect fulfilment of the Old Law (cf. Mt 5:17).

On Sinai, God remained on the summit of the mountain, which Moses had to climb to receive the tablets of the Law. Christ, conversely, came halfway down the mount to meet man and to give him the New Law Himself. Thus, one Law is enacted on a mountaintop, another on a mountainside. While on Sinai man had to rise to God, on the mount where Jesus made His sermon, God comes down to man.

On Sinai, the Almighty presented Himself amidst thunder, lightning, darkness and the deafening sound of the trumpet. On the mount, the Saviour sits among men, in an amenable, calm and peaceful setting, without remarkable manifestations of nature. On Sinai, the people were forbidden to touch the base of the mountain, under pain of death. On the mount, the crowd comes close to Jesus and can touch Him, for a power flows from Him that cures all.

On Sinai, Moses was given a code of law, a true penal code, with severe punishment for those who transgressed it; on the mount, Our Lord, with boundless mercy, shows the awards, benefits and wonders that God bestows on those who practice virtue and fulfil the Law. On Sinai, Moses represents the Law, serving as an example in its zealous fulfilment. On the mount, Jesus Christ is the perfect model of the law of goodness.

On Sinai, it was a common man, albeit one chosen by God, who went up to hear the divine precepts; on the mount, however, only the God-Man, Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Second Person of the Trinity Incarnate, could pronounce that Sermon, because only He as the Messiah, had the authority to perfect the Old Law.

Within this context of goodness, Jesus proclaims the Beatitudes, showing the heights to which a soul is able to ascend through the flourishing of the Holy Spirit’s gifts, yielding acts of heroic virtue. Such fruits may develop in an isolated manner, but generally, when a saint reaches full union with God, all the beatitudes occur in one single blooming. To be holy, then, means to be blessed in time and then in eternity.

Divine filiation confers a quality upon us

What, then, is this blessedness? In the second reading (1 Jn 3:1-3) of this Liturgy, an inspiring passage of the First Letter of St. John gives us the answer. This Apostle of Love, a master of spirituality who always tends to emphasize the supernatural life, reminds us of the value of being children of God: “See what love the Father has given us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are” (1 Jn 3:1a). In fact, with Baptism, while we continue to have the same human nature, with intelligence, will, and sensitivity, a quality is added to us: participation in the divine nature itself, which assumes us completely. Grace, St. Bonaventure explains, “is a gift that purifies, enlightens and perfects the soul; that gives it life, reforms and strengthens it; that elevates it, assimilates it and unites it to God, making it acceptable to Him. This is a gift of such kind that it is rightly called ‘the grace that makes pleasing.’” 6

Being a spiritual good, it cannot be seen by material eyes, for these capture only physical things; its presence is proven, rather, by its effects. St. Catherine of Siena, to whom Our Lord granted the grace of seeing the states of souls, declared to her confessor: “Father, if you could but see the splendour of a rational soul, I have no doubt that you would give your life a hundred times over for its salvation, for nothing in this world can match it in beauty.” 7

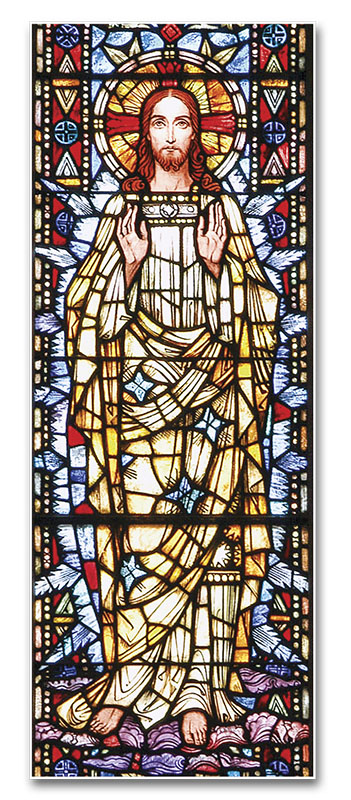

Certain images serve as a pale comparison for the wonders wrought in souls by grace. We may imagine a magnificent stained glass of perfectly combined hues, made from the highest quality glass, with gold added to its composition. Once set in place, if it receives no illumination, of what value is its spectacular design? However, from the moment a ray of light passes through it, it shines with extraordinary wealth of detail and scatters multicoloured reflections.

Another comparison that may bring us closer to the supernatural reality is that of a litre of alcohol into which is mixed a few drops of the finest essence of a superb fragrance. Without ceasing to be alcohol, the liquid becomes perfume, having been assumed by the essence.

Just as the light illuminates the stained glass and the essence assumes the alcohol—nature could also provide us with further illustrative images—grace confers a new quality upon the human soul, which is submerged, so to speak, into the divine nature, as Scheeben comments: “If, from among all men and all Angels God had chosen but one soul, to communicate to it the splendour of such an unexpected dignity, […] not only would mortals be left awestruck, but also the very Angels, who would almost feel tempted to worship it as though it were God Himself.”8 Such is the excellence of divine filiation!

The seed of future glory

Children of God… “And so we are. The reason why the world does not know us is that it did not know Him. Beloved, we are God’s children now; it does not yet appear what we shall be” (1 Jn 3:1b-2a). In fact, while in this world, in a state of trial, we have the sanctifying grace received in Baptism, and actual graces, which God pours out upon us throughout our lives. However, we are yet at the beginning of our journey; only when we contemplate God face to face, will grace be transformed into glory and will we reach “mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ” (Eph 4:13).

The idea of eternal happiness

This is absolute happiness, which our brethren, the Saints, enjoy fully in eternity and to which no consolation in this life is comparable. Our ideas surrounding happiness are so human that we may think we enjoy it to the maximum degree when we obtain something we really want. Mere human intelligence cannot comprehend heavenly happiness, for in relation to God we are like ants crawling along the earth, who raise their heads to look at an eagle soaring across the sky in full flight. The difference between an ant and an eagle is nothing compared with the infinity that separates human reason and divine intelligence. Even if we were extraordinarily gifted, and were to devote three hundred billion years to study, words would still fail us, and we would be unable to find adequate expressions to speak of God.

The divine essence is defined by theology as Self-subsisting Being,9 Who knows Himself, understands and loves Himself entirely, just as He is.10 From all eternity—that is, without beginning—God, beholding Himself, understands Himself completely as the uncreated Being, necessary and perfect, Who depends on no other, Who is self-sufficient, and in this consists His absolute happiness. However, His own knowledge is so rich that it begets a second Person, the Son, identical to Him and with the same happiness. They mutually love each other, and from this reciprocal love between Father and Son proceeds a Third Person, equally happy: the Holy Spirit. Thus, there are three Persons in one God, Who know, understand and love Themselves in perpetual joy, with neither beginning nor end, eternally!

A loan of divine intelligence

In His infinite love, God desired to grant intelligent creatures, Angels and men, a loan of His intellectual light, lumen gloriæ, which enables them to understand Him as He understands Himself—while maintaining due proportions between creature and Creator—since, according to St. Thomas, “the natural power of the created intellect does not avail to enable it to see the essence of God” unless it is amplified by “divine grace.”11 As much as He may mete out His light, He will always remain unchanged and undiminished, for He is infinite.

The eminent Dominican, Fr. Santiago Ramírez defines this lumen gloriæ as “an operative intellectual habit, infused per se, by which the understanding becomes deiform and prepared for intelligible union with the divine essence, rendering it capable of performing the act of beatific vision.”12

This “becoming deiform” means that those who enter eternal beatitude and contemplate God face to face become like Him, as St. John continues in his Epistle: “It does not yet appear what we shall be, but we know that when He appears we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is” (1 Jn 3:2b). Only in Heaven will we truly see Our Lord Jesus Christ, since during His life on this earth, no one saw Him as He really is. Not even during the Transfiguration, when He assumed, as a passing quality, the clarity inherent to the glorious body13 —as we have analyzed in previous commentaries—did St. Peter, St. James and St. John behold the essence of His divinity, for if they did, their souls would have left their bodies.

“And every one who thus hopes in Him purifies himself as He is pure” (1 Jn 1:3). The more the hope for this meeting and this vision increases in us, and therefore, the more we grow in our desire to surrender ourselves to God and belong entirely to Him in charity, the more we purify ourselves of the self-love and egoism so deeply rooted in our nature. We should be mindful that there are not three loves, but only two: love for God taken to self-forgetfulness or self-love carried to forgetfulness of God.14

III – Let Us Follow the Example of

Those Who Precede us in Grace and Await Us in Glory!

Man, even when deprived of grace, has an appetite for the infinite that does not rest until it is satisfied by union with God. St. Augustine asserts this in his Confessions: “Lo, You were within me and I without, and there did I seek You; deformed as I was, I rushed heedlessly among the beautiful things you have created. You were with me, but I was not with You; those things kept me far from You, which, unless they were in You, they were not at all.”15 5 This immense and indescribable happiness, for which we are all created, we will only reach following in the footsteps of those who have gone before us marked with the sign of faith and who now enjoy the reward for their faithfulness to this calling.

Let us ask that that we, too, may be privileged with eternal beatitude, through the merits of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the tears of Mary and the intercession of all the saints whom today we celebrate, so that we may join with them in Heaven. While we are on our way, we can interact with this vast multitude of celestial brethren, members of the same Body, by a direct channel—far more efficient than any other means of modern communication: prayer, love for God and for them, since they are united to God. We may be sure that, from above, they will look upon us with benevolence, pray for us and protect us. ◊

Notes